Selucius Garfielde on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Selucius Garfielde (December 8, 1822 – April 13, 1883) was an American lawyer and politician who was a

Garfielde was born in

Garfielde was born in

Garfielde next played a direct role in the organization of the

Garfielde next played a direct role in the organization of the

Delegate

Delegate or delegates may refer to:

* Delegate, New South Wales, a town in Australia

* Delegate (CLI), a computer programming technique

* Delegate (American politics), a representative in any of various political organizations

* Delegate (Unit ...

to the United States House of Representatives

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the Lower house, lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the United States Senate, Senate being ...

from the Territory of Washington

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

for two terms, serving from 1869 to 1873.

Early life

Garfielde was born in

Garfielde was born in Shoreham, Vermont

Shoreham is a town in Addison County, Vermont, United States. The population was 1,260 at the 2020 census.

Geography

Shoreham is located in western Addison County along the shore of Lake Champlain. The western boundary of the town, which follows ...

, on December 8, 1822. At some point in his life, Garfielde moved to Gallipolis, Ohio

Gallipolis ( ) is a chartered village in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Gallia County. The municipality is located in Southeast Ohio along the Ohio River about 55 miles southeast of Chillicothe and 44 miles northwest of Charlesto ...

, and then to Paris, Kentucky

Paris is a home rule-class city in Bourbon County, Kentucky. It lies northeast of Lexington on the Stoner Fork of the Licking River. Paris is the seat of its county and forms part of the Lexington–Fayette Metropolitan Statistical Area. As ...

. Sources say his relocation occurred "in early life", although whether this means in early childhood or in his late teens is unclear. He was educated in the public schools (where is unclear), and then graduated with a bachelor's degree

A bachelor's degree (from Middle Latin ''baccalaureus'') or baccalaureate (from Modern Latin ''baccalaureatus'') is an undergraduate academic degree awarded by colleges and universities upon completion of a course of study lasting three to six ...

from Augusta College. To earn money, he taught in public schools both before and after college.

Garfielde became a reporter in Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, and in 1849 was elected to the Kentucky Constitutional Convention as a delegate from Fleming County

Fleming County is a county located in the U.S. state of Kentucky. As of the 2020 census, the population was 15,082. Its county seat is Flemingsburg. The county was formed in 1798 and named for Colonel John Fleming, an Indian fighter and early s ...

. He traveled throughout South America

South America is a continent entirely in the Western Hemisphere and mostly in the Southern Hemisphere, with a relatively small portion in the Northern Hemisphere at the northern tip of the continent. It can also be described as the southe ...

in 1850 before finally settling in California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

in 1851. Upon his arrival, he was seriously ill and almost penniless. But he quickly recovered both his financial and physical health. In 1852, Garfielde was elected to the California State Assembly

The California State Assembly is the lower house of the California State Legislature, the upper house being the California State Senate. The Assembly convenes, along with the State Senate, at the California State Capitol in Sacramento.

The A ...

as a Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

from El Dorado County

El Dorado County (), officially the County of El Dorado, is a county located in the U.S. state of California. As of the 2020 census, the population was 191,185. The county seat is Placerville. The County is part of the Sacramento- Roseville-A ...

. He served a single term, from January 3 to May 19, 1853. Garfielde was appointed by the legislature to codify the laws of the state in 1853. During his tenure as a legislator, Garfielde became friends with Frederick H. Billings

Frederick H. Billings (September 27, 1823 – September 30, 1890) was an American lawyer, financier, and politician. He is best known for his legal work on land claims during the early years of California's statehood and his presidency of the ...

, a fellow attorney.

While serving in the legislature, Garfielde studied law. He was admitted to the State Bar of California

The State Bar of California is California's official attorney licensing agency. It is responsible for managing the admission of lawyers to the practice of law, investigating complaints of professional misconduct, prescribing appropriate disciplin ...

in 1854, and established a legal practice in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

. Garfielde married Sarah Electa Perry, also a native of Shoreham, Vermont, in October 1853. The couple had several children, including William Chase Garfield (no "e"), born in Kentucky in 1854, and Henry Stevens Garfield (no "e"), born in January 1860. The couple's second child, Mollie, died in November 1859 after just a few weeks of life. The couple's sixth child, Charles Darwin Garfield (no "e"), was born in February 1867 and became a widely known fur trader in Alaska

Alaska ( ; russian: Аляска, Alyaska; ale, Alax̂sxax̂; ; ems, Alas'kaaq; Yup'ik: ''Alaskaq''; tli, Anáaski) is a state located in the Western United States on the northwest extremity of North America. A semi-exclave of the U.S., ...

. He died in Seattle, Washington

Seattle ( ) is a port, seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the county seat, seat of King County, Washington, King County, Washington (state), Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in bo ...

, in September 1961.

Campaign of 1856 and Washington Territory

It is probable that Garfielde returned to Kentucky in 1854. Active in Democratic politics, he was elected a delegate to theDemocratic National Convention

The Democratic National Convention (DNC) is a series of presidential nominating conventions held every four years since 1832 by the United States Democratic Party. They have been administered by the Democratic National Committee since the 1852 ...

in 1856, where he became a supporter of Senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

Stephen A. Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which wa ...

. Douglas lost the Democratic nomination to James Buchanan

James Buchanan Jr. ( ; April 23, 1791June 1, 1868) was an American lawyer, diplomat and politician who served as the 15th president of the United States from 1857 to 1861. He previously served as secretary of state from 1845 to 1849 and repr ...

. Garfielde proved a loyal Democratic, however. During the election, Garfielde traveled heavily through what were then the western and northwestern states, delivering thousands of public speeches in support of Buchanan. He earned a wide reputation as a "captivating" public speaker. His service on the campaign trail left Kentucky Democrats feeling deeply in his debt.

Buchanan proved grateful to Garfielde for his campaign efforts, and appointed him Receiver of Public Monies for the Land Office in the Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

. Garfielde emigrated to Olympia

The name Olympia may refer to:

Arts and entertainment Film

* ''Olympia'' (1938 film), by Leni Riefenstahl, documenting the Berlin-hosted Olympic Games

* ''Olympia'' (1998 film), about a Mexican soap opera star who pursues a career as an athlet ...

, Washington Territory, that spring. Almost immediately, he became a supporter of Isaac Stevens

Isaac Ingalls Stevens (March 25, 1818 – September 1, 1862) was an American military officer and politician who served as governor of the Territory of Washington from 1853 to 1857, and later as its delegate to the United States House of Represe ...

, then campaigning for election as Washington Territory's first Territorial Delegate to Congress. When Stevens ran for re-election in 1858, Garfielde abandoned him early in the campaign. He feared that Stevens would lose the general election, jeopardizing Garfielde's position at the land office. By 1859, Garfielde's political views had shifted. A staunch Unionist, Garfielde (still a Democrat) now allied himself with the newly formed Republican Party. William Winlock Miller, a former prominent federal official in the Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

who had become an important businessman in the region, advised Stevens to deprive Garfielde of his land office position. Stevens attempted to do so in January 1860. But Democrats in Kentucky rallied to Garfielde's defense, forcing Stevens to hold off. By late May, however, Garfielde's support had withered in light of his pro-Republican activities, and Stevens was able to block Garfielde's reappointment. Garfielde's term as receiver of public moneys ended on August 16, 1860.

Garfielde sought the Democratic Party nomination for Territorial Delegate in 1861. Stevens saw unification of the Democratic Party as the only solution to the national crisis over slavery, which was threatening to tear the United States apart. Garfielde, however, broke with pro-secession Democrats, putting him at odds with Stevens. At the Democratic Party's territorial convention, pro-Union forces obtained a ruling from the chair that proxy votes could not be counted. This heavily damaged Stevens' chances for renomination as Territorial Delegate. After two rounds of balloting, some of Stevens' supporters became disgusted with their treatment by the chair and walked out. His candidacy crippled, Isaac Stevens withdrew his name from contention. The convention then split, with pro-Union forces nominating Garfielde and pro-secession forces nominating territorial judge Edward Lander. Republicans, meanwhile, nominated attorney William H. Wallace. Garfielde and Lander spent the campaign attacking one another, and on election day Wallace won election to Congress with 43 percent of the vote. Garfielde had 37.6 percent, and Lander 19.4 percent.

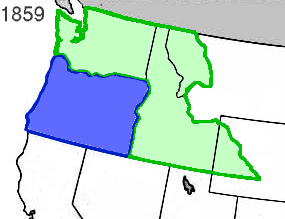

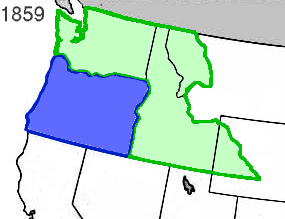

Creating Idaho Territory

Garfielde next played a direct role in the organization of the

Garfielde next played a direct role in the organization of the Idaho Territory

The Territory of Idaho was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 3, 1863, until July 3, 1890, when the final extent of the territory was admitted to the Union as Idaho.

History

1860s

The territory w ...

. The Washington Territory had originally been part of the vast Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

. But massive population growth north of the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

led to a divergence of interests between the northern southern parts of the territory. In 1853, the Washington Territory was split from the Oregon Territory. In 1859, Oregon was admitted as a U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sover ...

. That portion of the Oregon Territory not admitted as a state became part of the Washington Territory. That same year, gold was discovered in Idaho. By 1861, the cities of Pierce

Pierce may refer to:

Places Canada

* Pierce Range, a mountain range on Vancouver Island, British Columbia

United States

* Pierce, Colorado

* Pierce, Idaho

* Pierce, Illinois

* Pierce, Kentucky

* Pierce, Nebraska

* Pierce, Texas

* Pierce, We ...

and Oro Fino in the Idaho panhandle each had twice the population of either Olympia or Vancouver

Vancouver ( ) is a major city in western Canada, located in the Lower Mainland region of British Columbia. As the List of cities in British Columbia, most populous city in the province, the 2021 Canadian census recorded 662,248 people in the ...

on the Pacific coast. Major silver lodes were discovered that year at Silver City and Idaho City

Idaho City is a city in and the county seat of Boise County, Idaho, Boise County, Idaho, United States, located about northeast of Boise, Idaho, Boise. The population was 485 at the 2010 United States Census, 2010 census, up from 458 in 2000.

...

, leading to even greater population growth. Calls for local control of economic and political affairs grew stronger. In December 1861, the Washington Territory organized Idaho County and Nez Perce County out of the larger Shoshone County. Sentiment was growing that the economic interests of the mining area of Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

increasingly lacked commonality with the shipping and timber interests of Washington.

In the summer of 1862, Selucius Garfielde helped to create the Idaho Territory. During the Washington Territorial Delegate election in 1861, each candidate for office had pledged that if he were elected he would work for the creation of a new territory. In the summer of 1862, William H. Wallace called a conference of leading men at Oro Fino. Among them were Garfielde; Dr. Anson G. Henry, a physician and land surveyor; and George "Growler" Walker, an influential carpenter from Silver City. At what became known as the Oro Fino Conference, the group decided to seek organization of the Idaho Territory out of the eastern part of the Washington Territory and the western half of the Dakota Territory

The Territory of Dakota was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1861, until November 2, 1889, when the final extent of the reduced territory was split and admitted to the Union as the states of No ...

(which had been organized in 1861). The group's chances were good, as Dr. Henry had treated Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

for depression in 1841 and had remained Lincoln's good friend ever since. With Lincoln now president, Henry made the pitch for a new Idaho Territory. Lincoln agreed, and the new territory was duly organized by Congress on March 4, 1863.

Washington Territorial politics

During most of the period from 1862 to 1864, Garfielde lived inBritish Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

, Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

.

Garfielde switched political parties, becoming a Republican some time between November 1861 and January 1864. Garfielde continued to practice law, but he also continued to be actively involved in politics. In the Territorial Delegate election of 1864, he stumped throughout the territory for Republican candidate Arthur A. Denny

Arthur Armstrong Denny (June 20, 1822 – January 9, 1899) was one of the founders of Seattle, Washington,, Special Collections, Washington State Historical Society (WSHS). Accessed online 8 March 2008. the acknowledged leader of the pioneer Den ...

. By 1865, Garfielde could be counted among the top Republican contenders for any office he chose. In 1866, the Republicans denied Denny the nomination, choosing instead Alvan Flanders

Alvan Flanders (August 2, 1825 – March 14, 1894) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 8th governor of Washington Territory from 1869 to 1870. A member of the Republican, he previously served as the U.S. representative fo ...

. Garfielde's popularity was such that, at the beginning of the convention, even he received a few votes to be the party nominee.

President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

appointed him surveyor general of Washington Territory in 1866, and he served in that positioni until early 1869. Garfielde continued to have outside interests as well. About 1868, Garfielde joined with Daniel Bagley, P.H. Lewis, Josiah Settle, and George F. Whitworth to buy up several abandoned coal mining claims east of Seattle. They formed the Lake Washington Company, and won passage of legislation in the state legislature creating the Coal Creek Road Company. The road firm's goal was to build a road east to the coal fields. In 1870, the owners sold out to new investors, reaping a profit of 500 percent.

In 1868, Garfielde sought and won the Republican Party's nomination for Territorial Delegate. His nomination was not without problems. Garfielde's inconstant political views and his flowery oratory had alienated many, who felt he was a political opportunist. They nicknamed him "Selucius the Babbler". Opposition to Garfielde's nomination was so strong that Alvan Flanders

Alvan Flanders (August 2, 1825 – March 14, 1894) was an American businessman and politician who served as the 8th governor of Washington Territory from 1869 to 1870. A member of the Republican, he previously served as the U.S. representative fo ...

, the incumbent Territorial Delegate who had been denied renomination, and Christopher C. Hewitt, Chief Justice of the Washington Territorial Supreme Court, distributed a circular declaring the state Republican Party near collapse. They and the other signatories to the circular (which numbered more than 50 prominent Republicans) declared the party nomination process fraudulent and demanded radical reorganization of the party machinery. These and other accusations led to a significant backlash against the disaffected Republicans, who quickly retreated from their positions and declined to nominate their own candidate. The damage done, however, was significant. Garfielde won election over Marshall F. Moore by just 149 votes out of more than 5,300 cast. Due to a change in the date of the election, Garfielde's term of office lasted nearly three years. He began serving on March 4, 1869, but the House declined to seat him until December 1870. Garfielde won re-election to Congress in 1870 over Walla Walla Walla Walla can refer to:

* Walla Walla people, a Native American tribe after which the county and city of Walla Walla, Washington, are named

* Place of many rocks in the Australian Aboriginal Wiradjuri language, the origin of the name of the town ...

Democrat J.D. Mix by a more comfortable 735 votes out of more than 6,200 cast.

Garfielde lost re-election to Congress in 1872. Garfielde's desire to make money on outside business interests did not abate during his tenure in Congress. In 1871, Jay Cooke

Jay Cooke (August 10, 1821 – February 16, 1905) was an American financier who helped finance the Union war effort during the American Civil War and the postwar development of railroads in the northwestern United States. He is generally acknowle ...

, the investment banker who controlled the Northern Pacific Railway

The Northern Pacific Railway was a transcontinental railroad that operated across the northern tier of the western United States, from Minnesota to the Pacific Northwest. It was approved by Congress in 1864 and given nearly of land grants, whic ...

(NP), hired Garfielde to stump throughout the Washington Territory to promote the railway's interests among voters. Cooke hired Garfielde, in part, because he believed this would please Frederick Billings, then the head of the NP's land office. But Billings heartily disliked Garfield, accusing him of being "too much of a politician" and arguing that it was unseemly for a sitting member of Congress to engage in such blatant promotion of a specific business interest. Billings also believed that Garfielde had allied himself too closely to independent loggers who routinely stolen timber from NP forest lands. Garfielde believed his work for the railway and the loggers would win him the votes he needed for re-election. But Garfielde did not count on the massive influx of new voters into the Washington Territory, most of whom were Democrats. Garfielde was defeated in 1872 in his bid for a third term by Democrat Obadiah Benton McFadden

Obadiah Benton McFadden (November 18, 1815 – June 25, 1875) was an American attorney and politician in the Pacific Northwest. He was the 8th justice of the Oregon Supreme Court, temporarily serving on the court to replace Matthew Deady. A Penns ...

by 761 votes out of 7,700 cast. He left office on March 3, 1873.

Garfielde remained influential in Republican politics, however. President Ulysses S. Grant

Ulysses S. Grant (born Hiram Ulysses Grant ; April 27, 1822July 23, 1885) was an American military officer and politician who served as the 18th president of the United States from 1869 to 1877. As Commanding General, he led the Union Ar ...

, elected to a second term as President in November 1872, appointed him customs collector for the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

District on March 26, 1873. Garfielde left Washington, D.C., and moved to Seattle where he engaged in the practice of law and served as customs collector until June 22, 1874.

Washington, D.C., and death

Garfielde returned to Washington, D.C., shortly after losing his customs job. He established several gambling parlors in the city, and although frequently raided he never served jail time. Garfielde had long exhibited a number of habits, many of which—like gambling, heavy drinking, and womanizing—were considered bad if not outright immoral by good citizens of the day. By the late 1870s, Sarah Garfielde had had enough, and the couple divorced about 1879. Garfielde did not live long after his divorce. He married Nellie Homer, proprietress of a bar for the criminal element and down-and-out, in late 1881. Garfielde fell ill with bothpleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

in April 1883. He began deteriorating quickly on April 11, and died at his home at 410 10th Street NW at 5:30 p.m. on April 13. He was interred at Glenwood Cemetery. Although he was a Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Washington Territory, Masonic rites were not observed at his funeral as he had not affiliated with any lodge in the D.C. area.

References

;Notes ;CitationsBibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* (Garfielde's 20-page notes of a lecture he had given.) {{DEFAULTSORT:Garfielde, Selucius 1822 births 1881 deaths Members of the California State Assembly Delegates to the United States House of Representatives from Washington Territory People from Gallipolis, Ohio California Democrats Washington (state) Democrats Washington (state) Republicans 1856 United States presidential electors 19th-century American politicians People from Shoreham, Vermont Burials at Glenwood Cemetery (Washington, D.C.) Augusta College (Kentucky) alumni